- إنضم

- 1 يونيو 2014

- المشاركات

- 284

- مستوى التفاعل

- 263

- النقاط

- 63

Digital panopticon. The present and future of total surveillance of users.

The same panopticon.

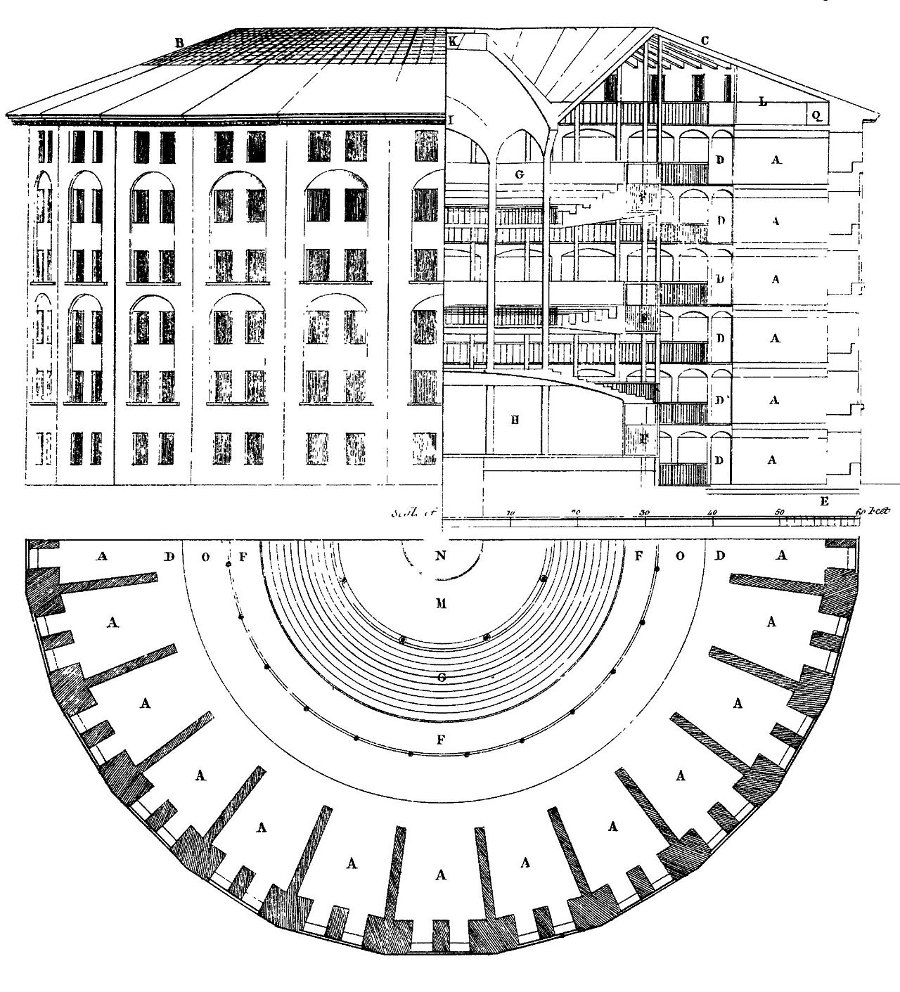

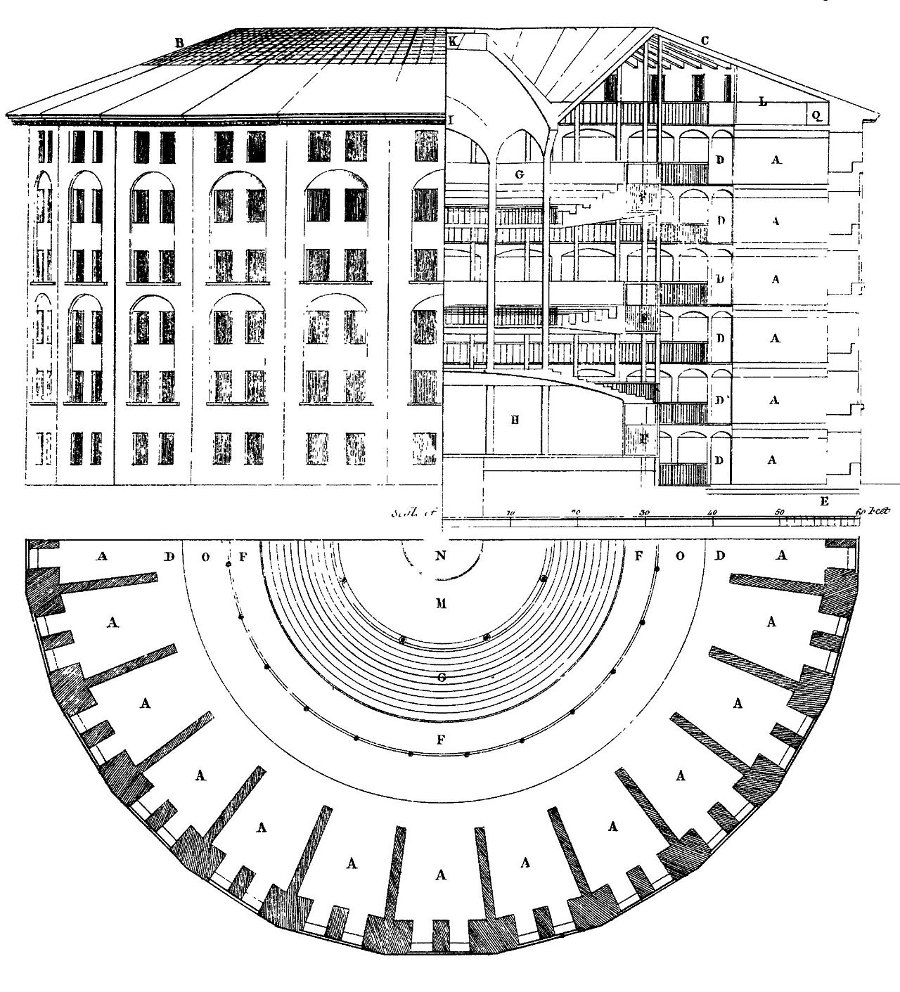

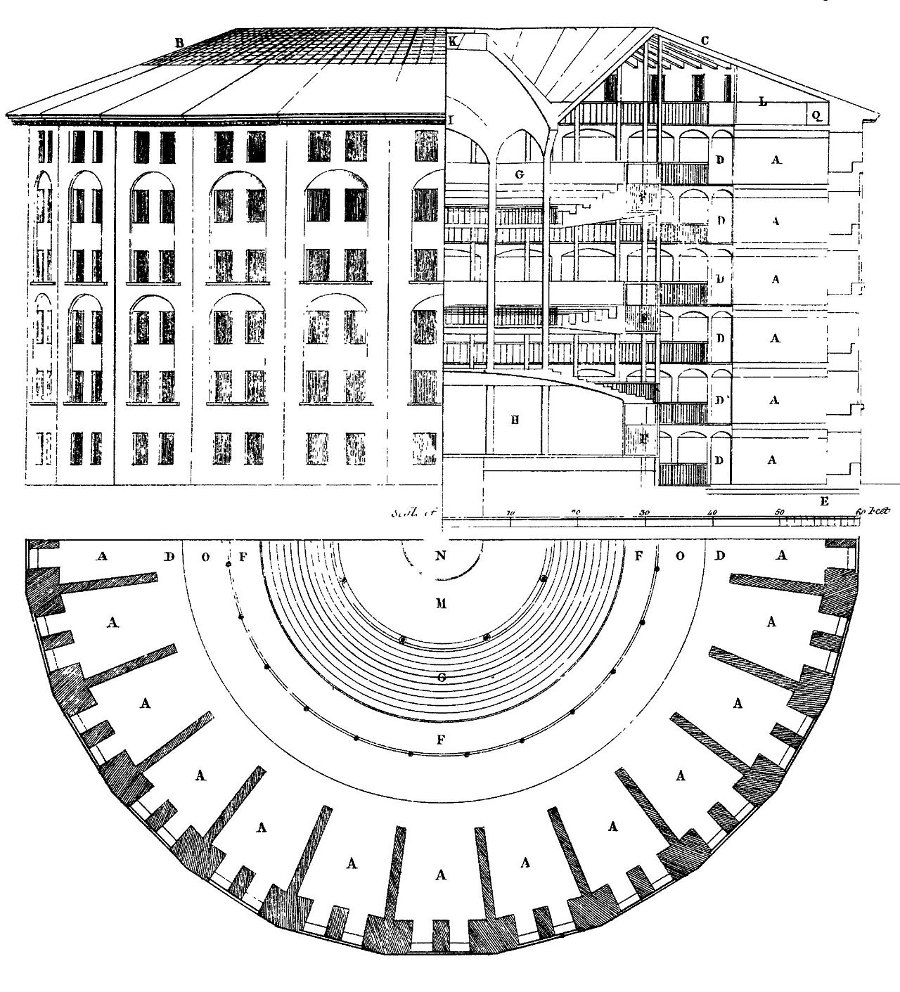

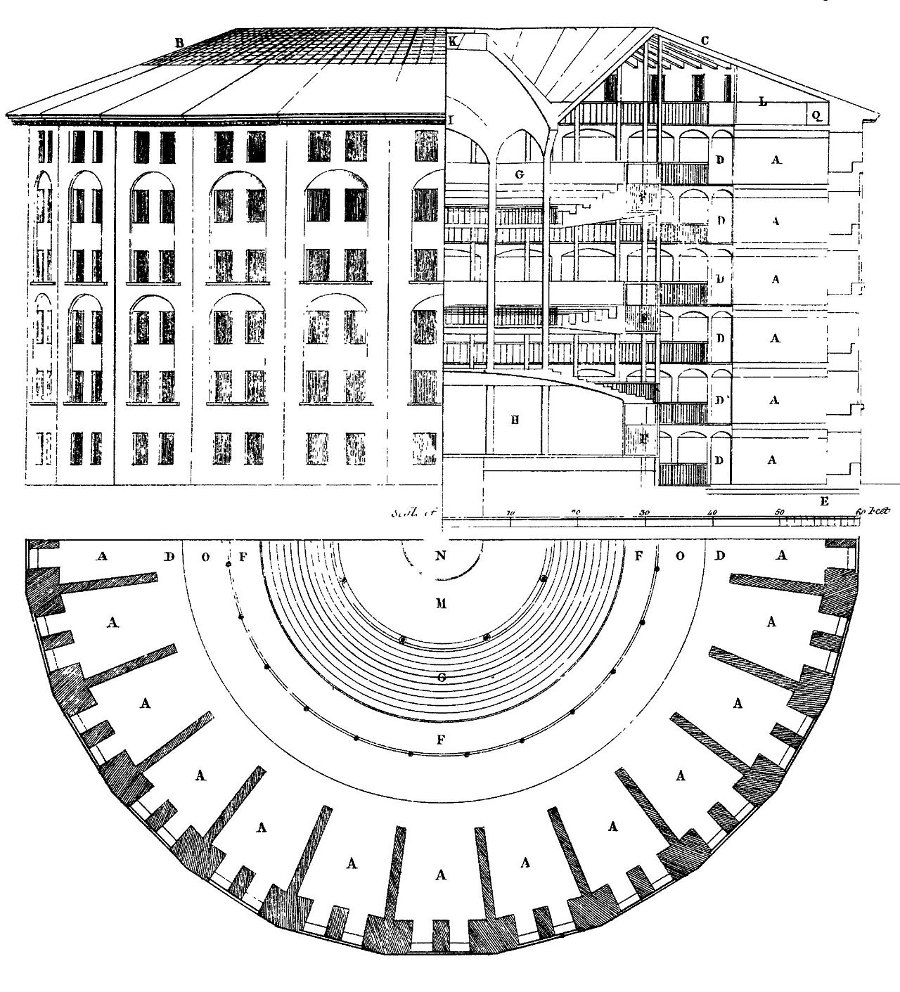

We will not start from the present, but from the eighteenth century, from which the word "panopticon" came to us. Initially, it was invented by the inventor of a rather strange thing - a prison in which the overseer could constantly see each prisoner, and the prisoners could not see each other or the overseer. Sounds like some kind of thought experiment or philosophical concept, right? In part, it is, but the author of this concept, Briton Jeremy Bentham, was extremely determined in his desire to build a panopticon in reality.

Bentamov drawings of the panopticon

Bentham was literally obsessed with his idea and for a long time begged the British and other governments to give him money to build a new type of prison. He believed that continuous and inconspicuous observation would have a positive effect on the correction of prisoners. Moreover, such prisons would be much cheaper to maintain. Towards the end, he himself was ready to become the chief overseer, but failed to raise money for the construction.

Panopticon-inspired prison in Cuba. Abandoned since 1967

Since then, several prisons and other institutions have been built in different countries, inspired by the drawings of Bentham. But we, of course, are interested in something else in this story.

The panopticon almost immediately became a synonym for a society of total surveillance and control. Which, it seems, is being built right before our eyes.

33 bits of entropy.

Researcher Arvind Narayanan has proposed a useful method that helps measure the degree of anonymity. He called it “33 bits of entropy” - that is how much information you need to know about a person in order to distinguish him in a unique way among the entire population of the Earth.

If we take some binary sign for each bit, then 33 bits will give us a unique match among 6.6 billion.

However, it should be remembered that signs are usually not binary and sometimes only a few parameters are enough.

Take, for example, the database where the zip code, gender, age and machine model are stored. The postal code limits the sample to an average of 20 thousand people - and this is a figure for a very densely populated city: in Moscow there are 10 thousand people per post office, and an average of 3.5 thousand in Russia.

Gender will limit sampling by half. The age is already up to several hundred, if not tens. And the model of the car is only up to a couple of people, and often up to one. A rarer car or smaller settlement may make half the parameters unnecessary.

Scripts, cookies and funny tricks.

Instead of a zip code and a machine model, you can use the browser version, operating system, screen resolution and other parameters that we leave for each visited site, and ad networks diligently collect all this and easily track the path, habits and preferences of individual users.

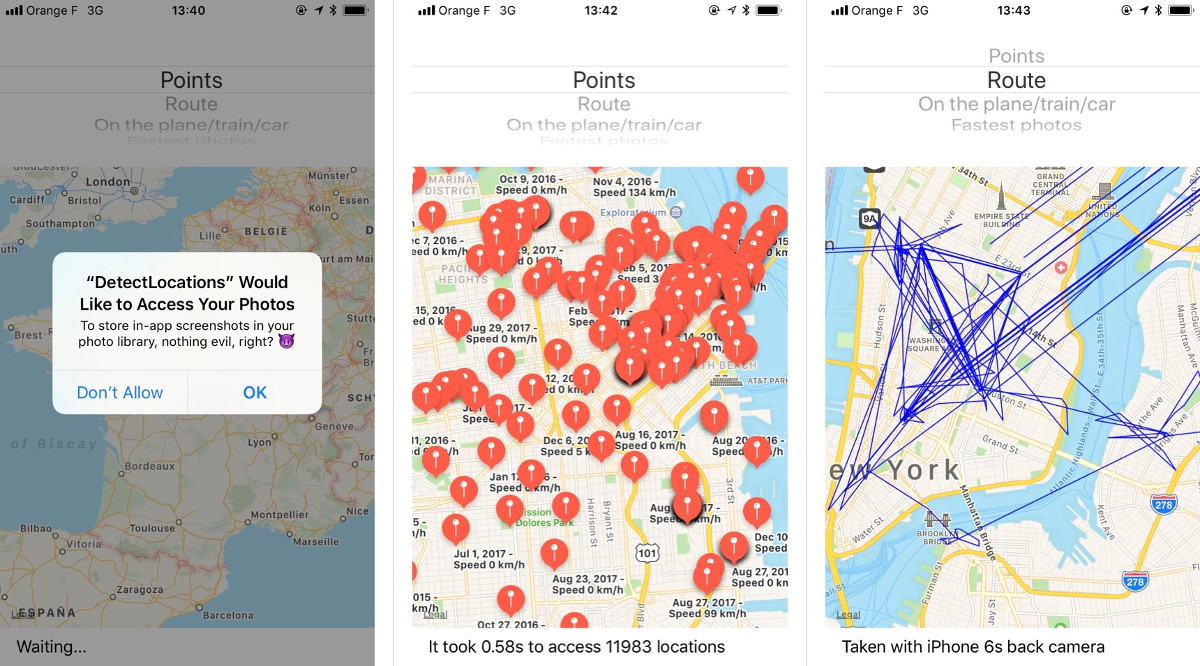

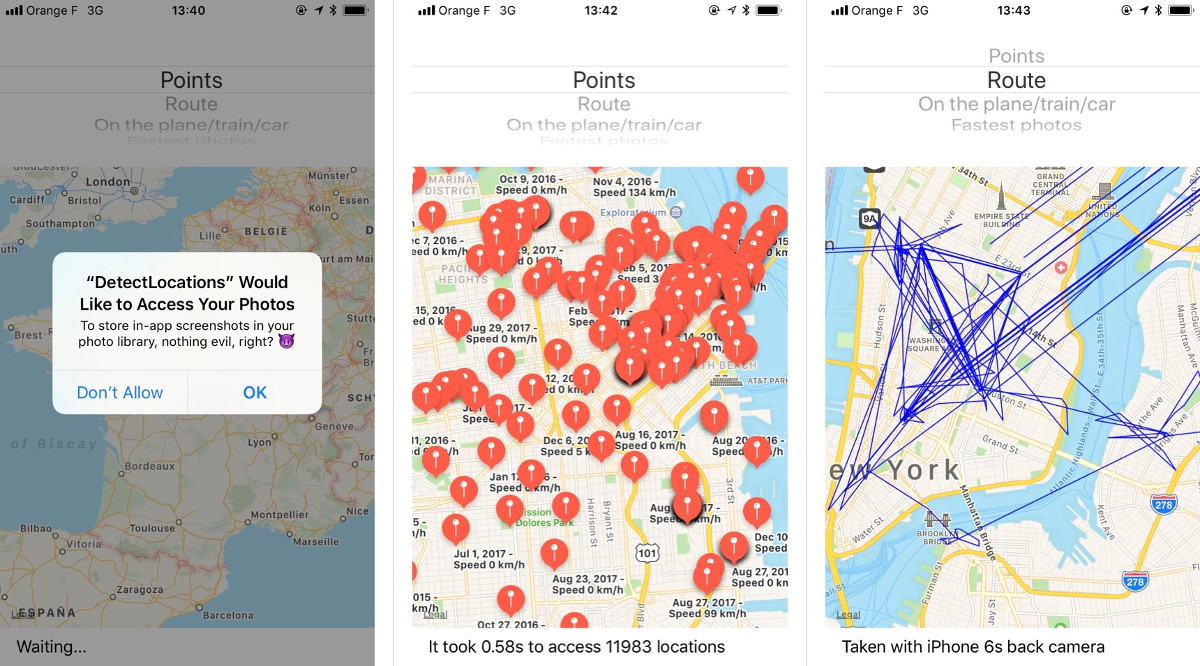

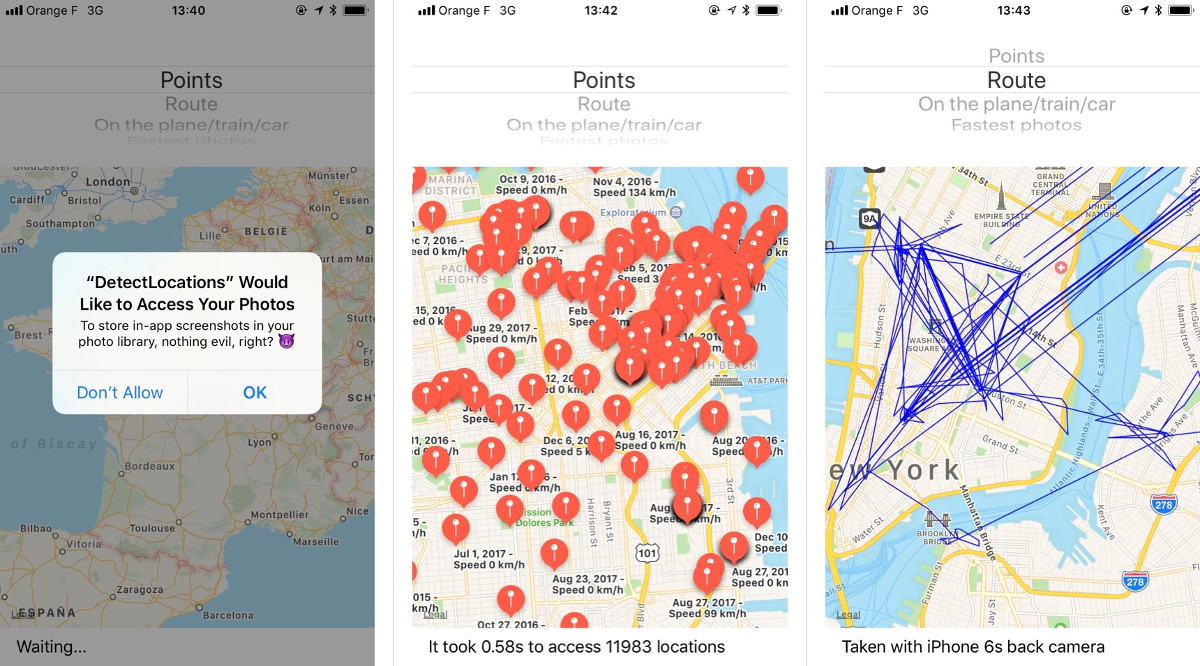

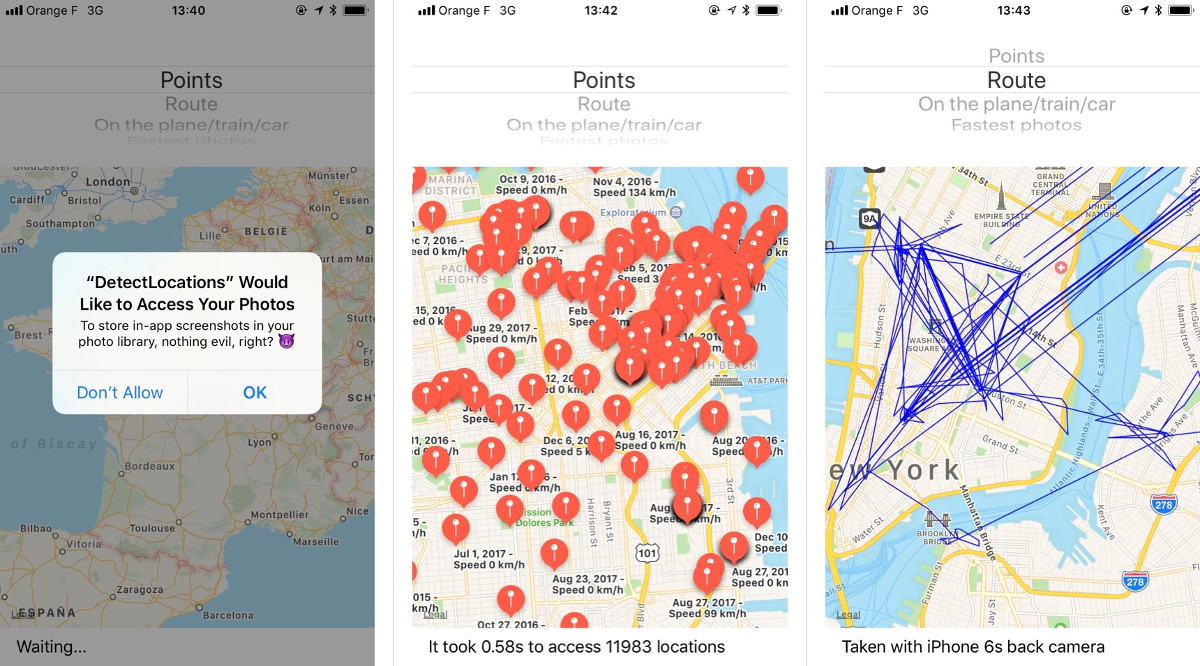

Here's a fun example from the world of mobile apps.

Each iOS program that gets access to photos (for example, to impose a beautiful effect on them) has the ability to scan the entire database in seconds and suck in the metadata. If there are a lot of photos, then from the data on geolocation and time of shooting it is easy to add the route of your movements over the past five years.

detect.location

There are more well-known, but no less unpleasant things.

For example, many attendance counters like Yandex.Metrica allow site owners, among other things, to record a user's session — that is, to write each mouse movement and click on a button. On the one hand, there is nothing illegal here, on the other hand, it’s worth seeing such a record with your own eyes, and you understand that there is something wrong and such a mechanism should not exist. And this is not counting the fact that passwords or payment data can leak through it in certain cases.

And there are a lot of such examples - if you are interested in the topic and read “Division K” for more than a couple of months, then you yourself can easily remember something in this spirit.

But it’s much more difficult to understand what happens to the collected data further. But their life is rich and interesting.

Traders habits.

Many of the data collected at first glance seems harmless and often anonymized, but it is not as difficult to connect it with a person as it seems, and harmlessness depends on the circumstances. Do you think it's safe to share pedometer data with someone, for example? According to them, in particular, it is easy to understand what time you are not at home and on what days you return late.

However, the robbers have not yet reached such high technologies, but advertisers may be interested in any information about your habits. How often do you go somewhere? On weekdays or on weekends? In the morning or in the afternoon? Which establishments? And so on and so forth.

In the United States alone, according to Newsweek magazine, there are several thousand companies that collect, process and sell databases (industry giants Acxiom and Experian operate in billions of dollars). Their main product is all sorts of ratings, which business owners can buy and use ready-made when making decisions.

There is no shortage of those wishing to sell data.

Any businessman who finds out that you can make some money out of nothing will at least be interested. And do not think that the main evil here is soulless corporations.

Startups in this regard are almost worse: today they have wonderful, honest people working in them, and tomorrow only a couple of cynical managers can be left, hammering out the latest property.

The author of Newsweek notes an important point: the data collected by brokers often contain errors and the rating may turn out to be incorrect. So if someone is suddenly denied a loan or doesn’t want to hire, then perhaps he should blame not himself, but an insane surveillance system that has spontaneously emerged over the past fifteen years.

Your shadow profile.

In most countries, the center of online social life is Facebook, and so conversations about privacy on the Web often revolve around it.

At first glance, it might seem that Facebook takes good care of the safety of personal data and provides a lot of privacy settings. Therefore, technically savvy people often write off the fears and complaints of less educated comrades in this regard. If someone accidentally shared with the world what they did not want to share, it means that he was to blame - he had to think with his head in time.

In reality, Facebook really cares about the safety of personal data, but this is rather a statement like the aphorism known in the USSR “We need peace, and, if possible, the whole.”

Like many social networks and instant messengers, Facebook is trying to capture and save as much personal data as possible.

it was noticed behind the Telegram . Here is a paradox: a messenger that, on the one hand, provides convenient encryption tools, on the other hand, doesn’t forget to capture everything it reaches.

Even more fun is that Facebook already has so much data that even if an individual has never had an account, his profile can still be composed of information that other people continuously leave. And “possible” in such cases means that it certainly happens. If the algorithms of the social network see an information hole in the form of a person, then they will have it in mind and supplement it with new details.

Facebook employees are terribly disliked by the phrase “shadow profile”. Of course, it's nice to think that they simply collect data that will help people find old friends, resume lost business contacts, and all that.

A little less pleasant is to remember that all this is done in order to sell advertising more effectively. And one doesn’t want to constantly imagine cases of blackmail, revenge or fraud.

In this case, it does not matter at all to us what Zuckerberg and his employees want. Yes, most likely, he regrets that at the dawn of his career he called the first Facebook users offensive words dumb fucks for the fact that they left personal data on his site. But have his views on life changed since then? And the more important question is - aren't his words becoming ever more truthful?

Not a very distant future.

Only ten to fifteen years ago, everything that we talked about here either did not exist, or most people did not care. Now the reaction of the public is slowly changing, but, most likely, not fast enough, and the next ten to fifteen years in terms of privacy promise to become extremely unpleasant (or private?).

If now it’s easiest to follow on the Internet, with the miniaturization and cheapening of electronics, the same problems will gradually get to the world around us. Actually, they are already slowly getting there, but this is only the beginning.

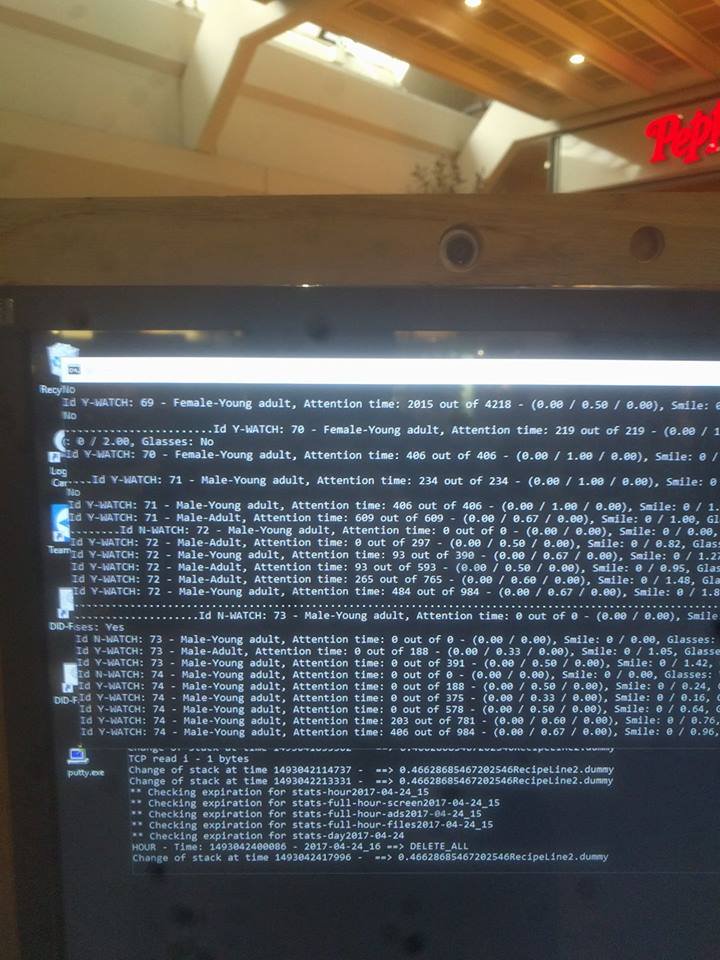

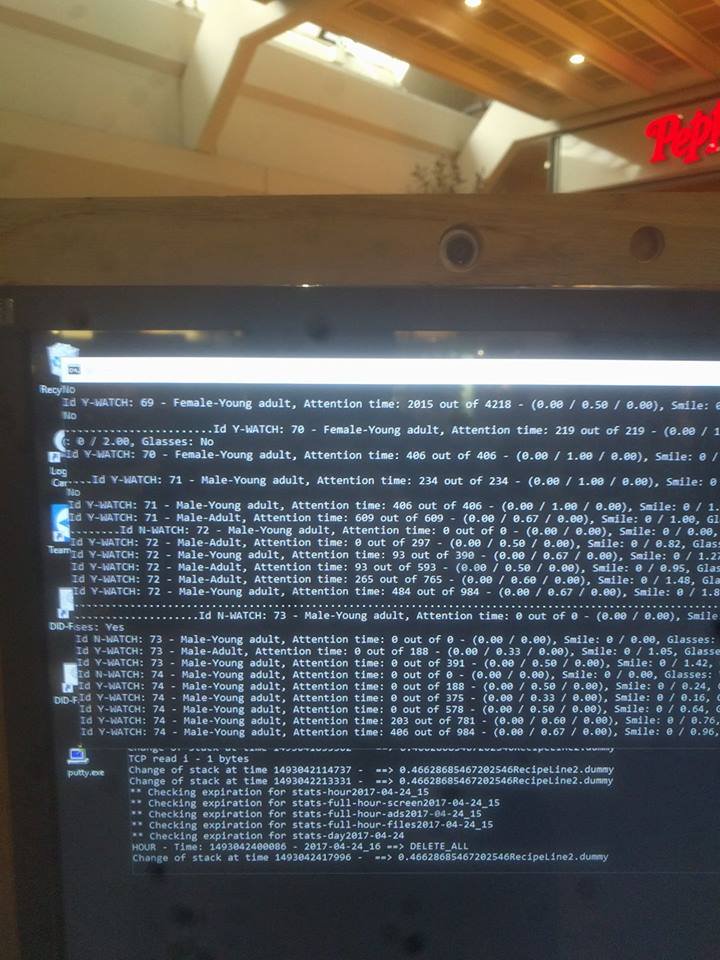

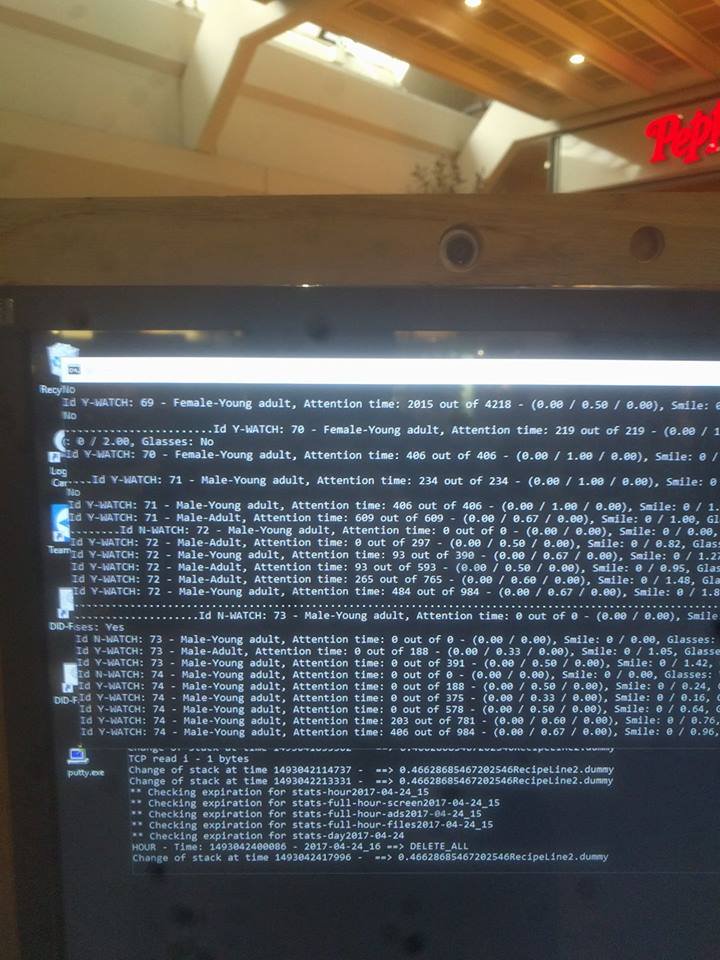

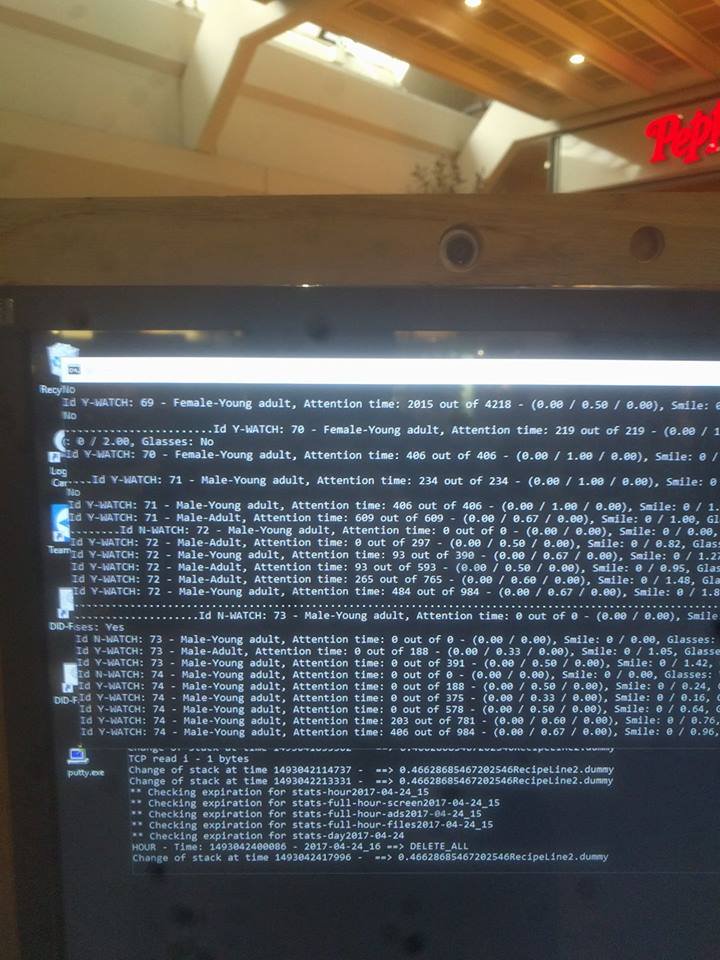

Recently, everyone was groaning and gasping from a photo of a malfunctioning advertising stand in a pizzeria that detected faces.

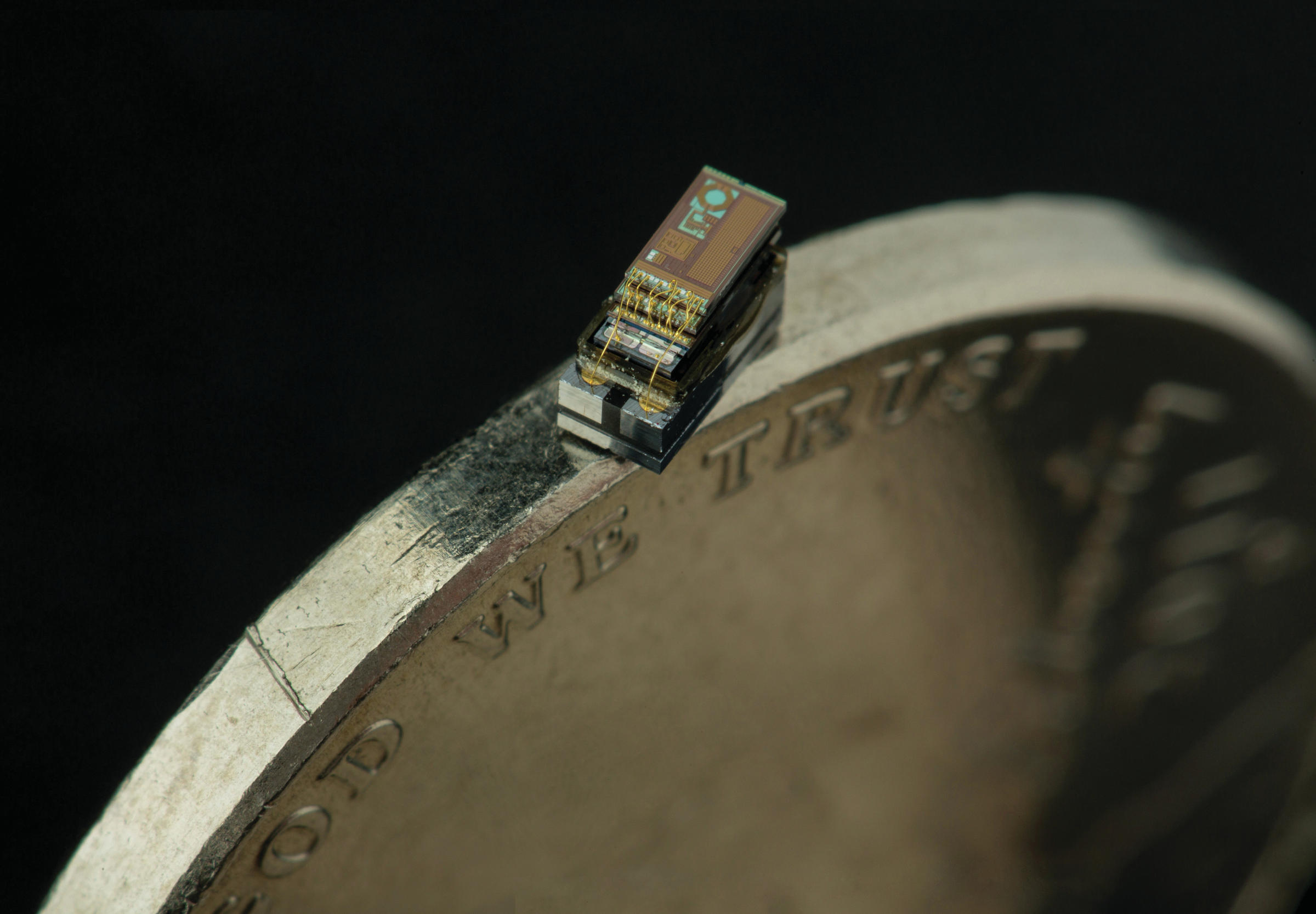

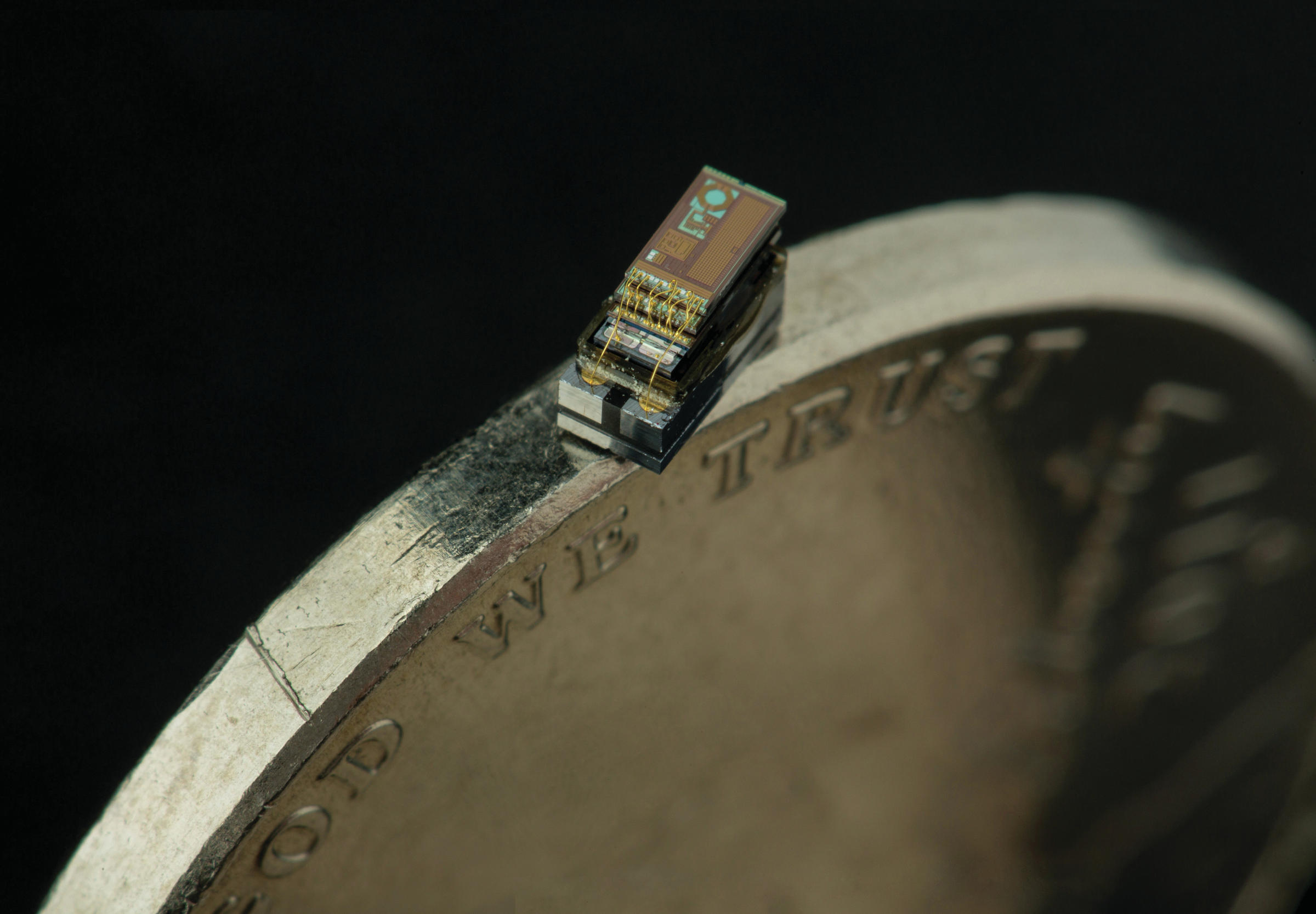

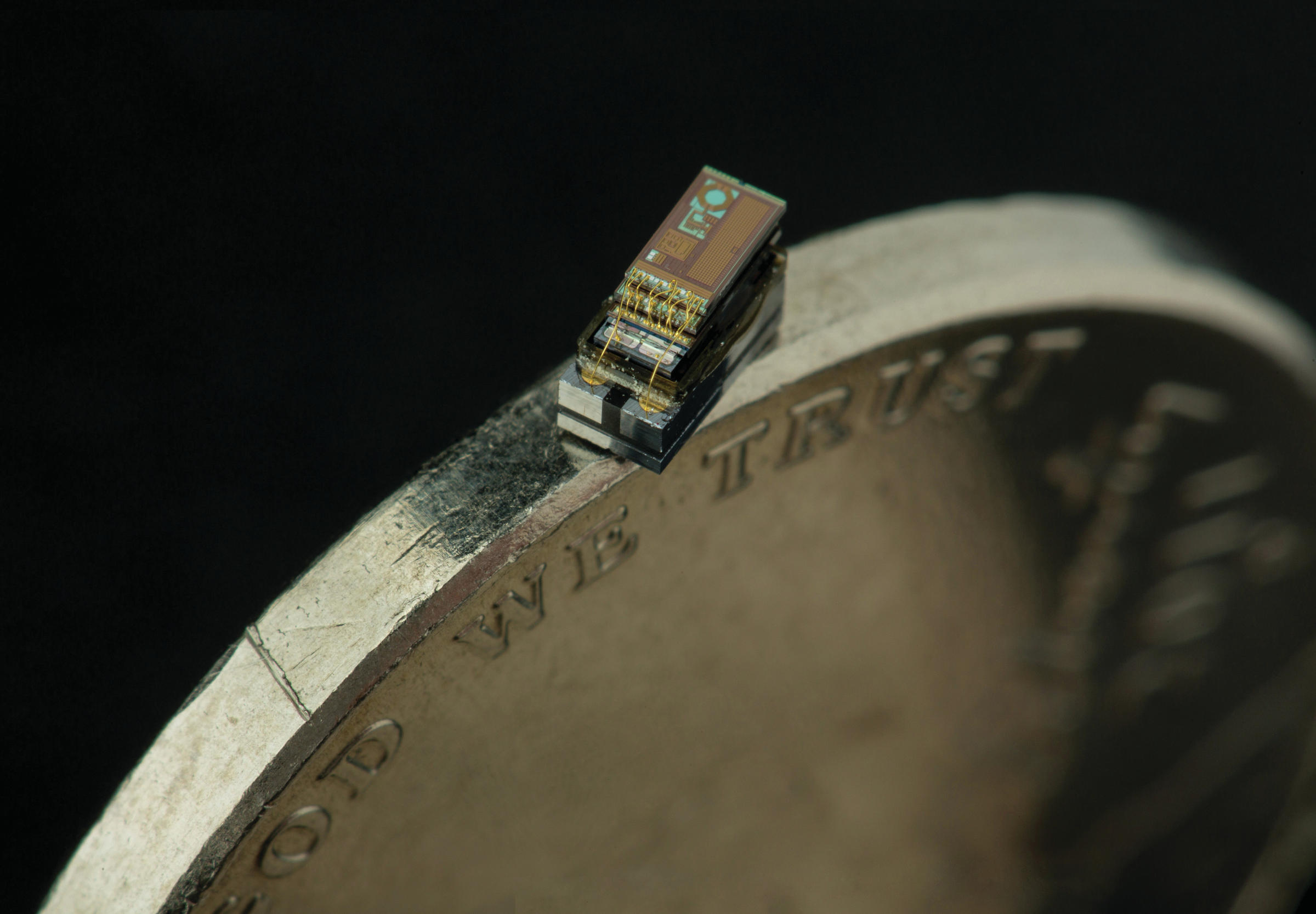

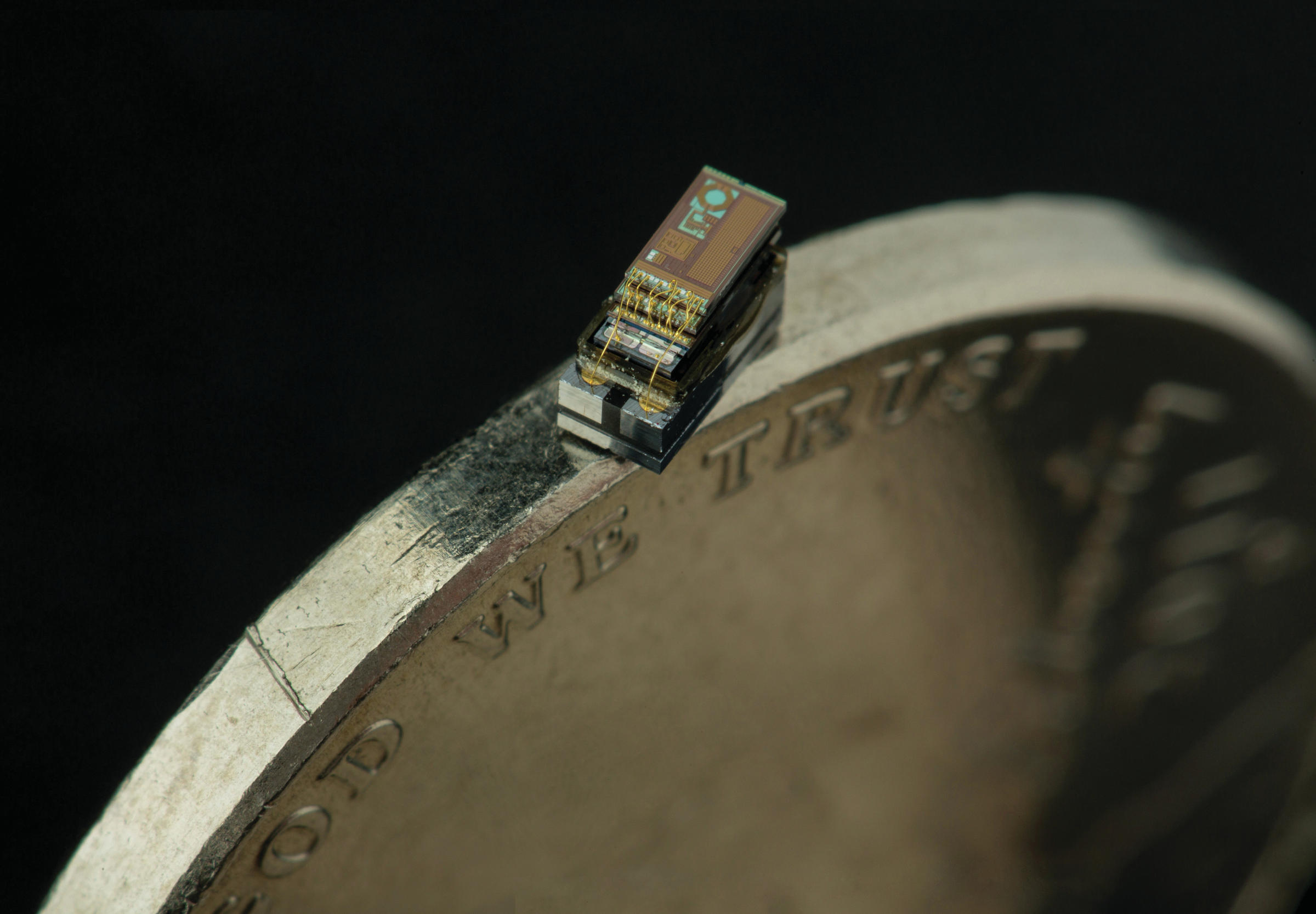

It was necessary to worry when this thing was transported to exhibitions. In the article “How low (power) can you go?” writer Charlie Strauss builds on the Kumi law (a variation of Moore’s law, which says that the energy efficiency of computers doubles every 18 months) and calculates the minimum power consumption of computers in 2032.

According to the rough estimates of Strauss, it turns out that in fifteen years the analogue of the current low-power mobile systems on a chip with a set of sensors will be able to be powered by a solar battery with a side of two to three millimeters or from the energy of the radio signal. And this does not take into account the fact that more efficient batteries or other methods of energy delivery may appear.

Strauss argues further: “We will assume that our hypothetical low-power computer in mass production will cost 10 cents apiece. Then covering London with processors one per square meter by 2040 will cost 150 million euros, or 20 euros per person. ” The same amount of the authorities in London in 2007 spent chewing gum off the roads, so it is unlikely that such a project would be too expensive for the city.

Michigan Micro Mote is a prototype of a tiny solar-powered computer. And this is the technology of 2015, and not the year 2034.

Next, Strauss discusses the benefits that can be gained by computerizing urban surfaces, from super-accurate weather forecasts to preventing epidemics. But in the framework of this article, of course, we are interested in something else: the level of total observation that this almost “smart dust” from science fiction can give.

"Wearing a hoodie will not help anymore," - Strauss notes sarcastically.

And indeed: even if the ubiquitous sensors do not have cameras, they can still read each RFID tag or identify mobile devices with communication modules. And actually, why there will be no cameras? Tiny lenses that can be produced right away with the sensor are already being created in the laboratory.

The memory of the crowd.

What can potentially lead to the spraying of computers in an even layer around the surrounding area, Strauss calls the words panopticon singularity - by analogy with technological singularity, which implies the uncontrolled spread of technology.

This is another man-made horror story, which means widespread observation and, as a result, lack of freedom.

One can imagine to what extremes it will go if mass surveillance technologies fall into the hands of a dictatorial regime or religious fundamentalists. However, even if one imagines that such a system will be controlled by the ordinary government, which is not particularly corrupt and not too fixated on traditional values, it is still somehow uncomfortable.

Another potential source of ubiquitous surveillance is the people themselves. Here is a brief history of this technology:

There may be different reasons to attach a camera to your head - for example, to stream in Periscope or Twitch, use applications with augmented reality or simply record everything that happens in order to have a digital copy that you can turn to for memory at any time.

Gordon Bell, a senior researcher at Microsoft Research, in his latest book, Your Life Uploaded Bell, talks about different aspects of society, where everyone has documentary evidence of what happened. Bell believes that this is good: there will be no crime, there will be no innocently punished, and people will be able to use the highly reliable memory of the machines.

But what about privacy? Is it possible in the future world to do something secretly from others?

Bell believes that the system should be built in such a way that at any time you can exclude yourself from public memory.

You press the magic button, and the right to watch the recording with you will remain, for example, only with the police. Convenient, right?

This is where you really understand where the road that Facebook with its shadow profiles has come to end with. If everything will be as it is now and people will continue to joyfully upload their data, then the magic button for dropping out of the shared memory simply will not affect anything. Well, you excluded yourself, and the intelligent algorithm immediately connected everything back from indirect signs.

What to do?

... so that a dark future does not come, from which even George Orwell would flinch?

We all think that probably someone out there somehow will take care of this. Activists must say no, governments must introduce laws, the executive branch must follow, and so on. Alas, a lot of cases are known in history when this scheme did not fail mildly.

Government initiatives do exist - see, for example, the European GDPR - the general data protection regulation.

This decree regulates the collection and storage of personal information, and with it Facebook no longer escapes with a sparing (taking into account gigantic turnovers) fine of 122 million euros. It will have to roll off already 4% of revenue, that is, at least a billion.

The first stage of GDPR starts on May 25, 2018. Then we will find out what side effects he has, what kind of workarounds will follow and whether in reality something will be achieved from transnational corporations. In Russia, there is already not the most successful experience with the law “On Personal Data”. It is characteristic that his modest successes make few people sad (“let Zuckerberg and Page and Brin better follow than Comrade Colonel”).

On the whole, there are serious suspicions that governments do not want to stop snooping so much as to attach to it, but ideally - to regain their monopoly.

So it would be much better if the corporations started pulling and regulating themselves. Alas, as we see on the example of Facebook, some of them work in exactly the opposite direction.

Can we do something ourselves, except to frantically try to hide, encrypt, obfuscate and turn off everything in the world? I suggest starting with the main thing - try never to wave your hand and never say: “Ay, everyone is watching anyway!” Not all the same, not all and not with the same consequences. It is important.

Source @dapartamentK

The same panopticon.

We will not start from the present, but from the eighteenth century, from which the word "panopticon" came to us. Initially, it was invented by the inventor of a rather strange thing - a prison in which the overseer could constantly see each prisoner, and the prisoners could not see each other or the overseer. Sounds like some kind of thought experiment or philosophical concept, right? In part, it is, but the author of this concept, Briton Jeremy Bentham, was extremely determined in his desire to build a panopticon in reality.

Bentamov drawings of the panopticon

Bentham was literally obsessed with his idea and for a long time begged the British and other governments to give him money to build a new type of prison. He believed that continuous and inconspicuous observation would have a positive effect on the correction of prisoners. Moreover, such prisons would be much cheaper to maintain. Towards the end, he himself was ready to become the chief overseer, but failed to raise money for the construction.

Panopticon-inspired prison in Cuba. Abandoned since 1967

Since then, several prisons and other institutions have been built in different countries, inspired by the drawings of Bentham. But we, of course, are interested in something else in this story.

The panopticon almost immediately became a synonym for a society of total surveillance and control. Which, it seems, is being built right before our eyes.

33 bits of entropy.

Researcher Arvind Narayanan has proposed a useful method that helps measure the degree of anonymity. He called it “33 bits of entropy” - that is how much information you need to know about a person in order to distinguish him in a unique way among the entire population of the Earth.

If we take some binary sign for each bit, then 33 bits will give us a unique match among 6.6 billion.

However, it should be remembered that signs are usually not binary and sometimes only a few parameters are enough.

Take, for example, the database where the zip code, gender, age and machine model are stored. The postal code limits the sample to an average of 20 thousand people - and this is a figure for a very densely populated city: in Moscow there are 10 thousand people per post office, and an average of 3.5 thousand in Russia.

Gender will limit sampling by half. The age is already up to several hundred, if not tens. And the model of the car is only up to a couple of people, and often up to one. A rarer car or smaller settlement may make half the parameters unnecessary.

Scripts, cookies and funny tricks.

Instead of a zip code and a machine model, you can use the browser version, operating system, screen resolution and other parameters that we leave for each visited site, and ad networks diligently collect all this and easily track the path, habits and preferences of individual users.

Here's a fun example from the world of mobile apps.

Each iOS program that gets access to photos (for example, to impose a beautiful effect on them) has the ability to scan the entire database in seconds and suck in the metadata. If there are a lot of photos, then from the data on geolocation and time of shooting it is easy to add the route of your movements over the past five years.

detect.location

There are more well-known, but no less unpleasant things.

For example, many attendance counters like Yandex.Metrica allow site owners, among other things, to record a user's session — that is, to write each mouse movement and click on a button. On the one hand, there is nothing illegal here, on the other hand, it’s worth seeing such a record with your own eyes, and you understand that there is something wrong and such a mechanism should not exist. And this is not counting the fact that passwords or payment data can leak through it in certain cases.

And there are a lot of such examples - if you are interested in the topic and read “Division K” for more than a couple of months, then you yourself can easily remember something in this spirit.

But it’s much more difficult to understand what happens to the collected data further. But their life is rich and interesting.

Traders habits.

Many of the data collected at first glance seems harmless and often anonymized, but it is not as difficult to connect it with a person as it seems, and harmlessness depends on the circumstances. Do you think it's safe to share pedometer data with someone, for example? According to them, in particular, it is easy to understand what time you are not at home and on what days you return late.

However, the robbers have not yet reached such high technologies, but advertisers may be interested in any information about your habits. How often do you go somewhere? On weekdays or on weekends? In the morning or in the afternoon? Which establishments? And so on and so forth.

In the United States alone, according to Newsweek magazine, there are several thousand companies that collect, process and sell databases (industry giants Acxiom and Experian operate in billions of dollars). Their main product is all sorts of ratings, which business owners can buy and use ready-made when making decisions.

There is no shortage of those wishing to sell data.

Any businessman who finds out that you can make some money out of nothing will at least be interested. And do not think that the main evil here is soulless corporations.

Startups in this regard are almost worse: today they have wonderful, honest people working in them, and tomorrow only a couple of cynical managers can be left, hammering out the latest property.

The author of Newsweek notes an important point: the data collected by brokers often contain errors and the rating may turn out to be incorrect. So if someone is suddenly denied a loan or doesn’t want to hire, then perhaps he should blame not himself, but an insane surveillance system that has spontaneously emerged over the past fifteen years.

Your shadow profile.

In most countries, the center of online social life is Facebook, and so conversations about privacy on the Web often revolve around it.

At first glance, it might seem that Facebook takes good care of the safety of personal data and provides a lot of privacy settings. Therefore, technically savvy people often write off the fears and complaints of less educated comrades in this regard. If someone accidentally shared with the world what they did not want to share, it means that he was to blame - he had to think with his head in time.

In reality, Facebook really cares about the safety of personal data, but this is rather a statement like the aphorism known in the USSR “We need peace, and, if possible, the whole.”

Like many social networks and instant messengers, Facebook is trying to capture and save as much personal data as possible.

it was noticed behind the Telegram . Here is a paradox: a messenger that, on the one hand, provides convenient encryption tools, on the other hand, doesn’t forget to capture everything it reaches.

Even more fun is that Facebook already has so much data that even if an individual has never had an account, his profile can still be composed of information that other people continuously leave. And “possible” in such cases means that it certainly happens. If the algorithms of the social network see an information hole in the form of a person, then they will have it in mind and supplement it with new details.

Facebook employees are terribly disliked by the phrase “shadow profile”. Of course, it's nice to think that they simply collect data that will help people find old friends, resume lost business contacts, and all that.

A little less pleasant is to remember that all this is done in order to sell advertising more effectively. And one doesn’t want to constantly imagine cases of blackmail, revenge or fraud.

In this case, it does not matter at all to us what Zuckerberg and his employees want. Yes, most likely, he regrets that at the dawn of his career he called the first Facebook users offensive words dumb fucks for the fact that they left personal data on his site. But have his views on life changed since then? And the more important question is - aren't his words becoming ever more truthful?

Not a very distant future.

Only ten to fifteen years ago, everything that we talked about here either did not exist, or most people did not care. Now the reaction of the public is slowly changing, but, most likely, not fast enough, and the next ten to fifteen years in terms of privacy promise to become extremely unpleasant (or private?).

If now it’s easiest to follow on the Internet, with the miniaturization and cheapening of electronics, the same problems will gradually get to the world around us. Actually, they are already slowly getting there, but this is only the beginning.

Recently, everyone was groaning and gasping from a photo of a malfunctioning advertising stand in a pizzeria that detected faces.

It was necessary to worry when this thing was transported to exhibitions. In the article “How low (power) can you go?” writer Charlie Strauss builds on the Kumi law (a variation of Moore’s law, which says that the energy efficiency of computers doubles every 18 months) and calculates the minimum power consumption of computers in 2032.

According to the rough estimates of Strauss, it turns out that in fifteen years the analogue of the current low-power mobile systems on a chip with a set of sensors will be able to be powered by a solar battery with a side of two to three millimeters or from the energy of the radio signal. And this does not take into account the fact that more efficient batteries or other methods of energy delivery may appear.

Strauss argues further: “We will assume that our hypothetical low-power computer in mass production will cost 10 cents apiece. Then covering London with processors one per square meter by 2040 will cost 150 million euros, or 20 euros per person. ” The same amount of the authorities in London in 2007 spent chewing gum off the roads, so it is unlikely that such a project would be too expensive for the city.

Michigan Micro Mote is a prototype of a tiny solar-powered computer. And this is the technology of 2015, and not the year 2034.

Next, Strauss discusses the benefits that can be gained by computerizing urban surfaces, from super-accurate weather forecasts to preventing epidemics. But in the framework of this article, of course, we are interested in something else: the level of total observation that this almost “smart dust” from science fiction can give.

"Wearing a hoodie will not help anymore," - Strauss notes sarcastically.

And indeed: even if the ubiquitous sensors do not have cameras, they can still read each RFID tag or identify mobile devices with communication modules. And actually, why there will be no cameras? Tiny lenses that can be produced right away with the sensor are already being created in the laboratory.

The memory of the crowd.

What can potentially lead to the spraying of computers in an even layer around the surrounding area, Strauss calls the words panopticon singularity - by analogy with technological singularity, which implies the uncontrolled spread of technology.

This is another man-made horror story, which means widespread observation and, as a result, lack of freedom.

One can imagine to what extremes it will go if mass surveillance technologies fall into the hands of a dictatorial regime or religious fundamentalists. However, even if one imagines that such a system will be controlled by the ordinary government, which is not particularly corrupt and not too fixated on traditional values, it is still somehow uncomfortable.

Another potential source of ubiquitous surveillance is the people themselves. Here is a brief history of this technology:

- version 1.0 - old women at the entrance who know everything about everyone;

- version 2.0 - passers-by, who almost grab phones from their pockets, take pictures and post on social networks;

- version 3.0 - constantly turned on cameras on everyone’s head.

There may be different reasons to attach a camera to your head - for example, to stream in Periscope or Twitch, use applications with augmented reality or simply record everything that happens in order to have a digital copy that you can turn to for memory at any time.

Gordon Bell, a senior researcher at Microsoft Research, in his latest book, Your Life Uploaded Bell, talks about different aspects of society, where everyone has documentary evidence of what happened. Bell believes that this is good: there will be no crime, there will be no innocently punished, and people will be able to use the highly reliable memory of the machines.

But what about privacy? Is it possible in the future world to do something secretly from others?

Bell believes that the system should be built in such a way that at any time you can exclude yourself from public memory.

You press the magic button, and the right to watch the recording with you will remain, for example, only with the police. Convenient, right?

This is where you really understand where the road that Facebook with its shadow profiles has come to end with. If everything will be as it is now and people will continue to joyfully upload their data, then the magic button for dropping out of the shared memory simply will not affect anything. Well, you excluded yourself, and the intelligent algorithm immediately connected everything back from indirect signs.

What to do?

... so that a dark future does not come, from which even George Orwell would flinch?

We all think that probably someone out there somehow will take care of this. Activists must say no, governments must introduce laws, the executive branch must follow, and so on. Alas, a lot of cases are known in history when this scheme did not fail mildly.

Government initiatives do exist - see, for example, the European GDPR - the general data protection regulation.

This decree regulates the collection and storage of personal information, and with it Facebook no longer escapes with a sparing (taking into account gigantic turnovers) fine of 122 million euros. It will have to roll off already 4% of revenue, that is, at least a billion.

The first stage of GDPR starts on May 25, 2018. Then we will find out what side effects he has, what kind of workarounds will follow and whether in reality something will be achieved from transnational corporations. In Russia, there is already not the most successful experience with the law “On Personal Data”. It is characteristic that his modest successes make few people sad (“let Zuckerberg and Page and Brin better follow than Comrade Colonel”).

On the whole, there are serious suspicions that governments do not want to stop snooping so much as to attach to it, but ideally - to regain their monopoly.

So it would be much better if the corporations started pulling and regulating themselves. Alas, as we see on the example of Facebook, some of them work in exactly the opposite direction.

Can we do something ourselves, except to frantically try to hide, encrypt, obfuscate and turn off everything in the world? I suggest starting with the main thing - try never to wave your hand and never say: “Ay, everyone is watching anyway!” Not all the same, not all and not with the same consequences. It is important.

Source @dapartamentK

Original message

Original message

Цифровой паноптикон. Настоящее и будущее тотальной слежки за пользователями.

Тот самый паноптикон.

Начнем мы не с современности, а с восемнадцатого века, из которого к нам пришло слово «паноптикон». Изначально его придумал изобретатель довольно странной вещи — тюрьмы, в которой надзиратель мог постоянно видеть каждого заключенного, а заключенные не могли бы видеть ни друг друга, ни надзирателя. Звучит как какой-то мысленный эксперимент или философская концепция, правда? Отчасти так и есть, но автор этого понятия британец Джереми Бентам был настроен предельно решительно в своем стремлении построить паноптикон в реальности.

Бентамовские чертежи паноптикона

Бентам был буквально одержим своей идеей и долго упрашивал британское и другие правительства дать ему денег на строительство тюрьмы нового типа. Он считал, что непрерывное и незаметное наблюдение положительно скажется на исправлении заключенных. К тому же такие тюрьмы было бы намного дешевле содержать. Под конец он уже и сам был готов стать главным надзирателем, но денег на строительство собрать так и не удалось.

Вдохновленная паноптиконом тюрьма на Кубе. Заброшена с 1967 года

С тех пор в разных странах было построено несколько тюрем и других заведений, вдохновленных чертежами Бентама. Но нас в этой истории, конечно, интересует другое.

Паноптикон почти сразу стал синонимом для общества тотальной слежки и контроля. Которое, кажется, строится прямо у нас на глазах.

33 бита энтропии.

Исследователь Арвинд Нараянан предложил полезный метод, который помогает измерить степень анонимности. Он назвал его «33 бита энтропии» — именно столько информации нужно знать о человеке, чтобы выделить его уникальным образом среди всего населения Земли.

Если взять за каждый бит какой-то двоичный признак, то 33 бита как раз дадут нам уникальное совпадение среди 6,6 миллиарда.

Однако следует помнить о том, что признаки обычно не двоичны и иногда достаточно всего нескольких параметров.

Возьмем для примера базу данных, где хранится почтовый индекс, пол, возраст и модель машины. Почтовый индекс ограничивает выборку в среднем до 20 тысяч человек — и это цифра для очень плотно населенного города: в Москве на одно почтовое отделение приходится 10 тысяч человек, а в среднем по России — 3,5 тысячи.

Пол ограничит выборку вдвое. Возраст — уже до нескольких сотен, если не десятков. А модель машины — всего до пары человек, а зачастую и до одного. Более редкая машина или мелкий населенный пункт могут сделать половину параметров ненужными.

Скрипты, куки и веселые трюки.

Вместо почтового индекса и модели машины можно использовать версию браузера, операционную систему, разрешение экрана и прочие параметры, которые мы оставляем каждому посещенному сайту, а рекламные сети усердно все это собирают и с легкостью отслеживают путь, привычки и предпочтения отдельных пользователей.

Вот занятный пример из мира мобильных приложений.

Каждая программа для iOS, которая получает доступ к фотографиям (например, чтобы наложить на них красивый эффект), имеет возможность за секунды просканировать всю базу и засосать метаданные. Если фотографий много, то из данных о геолокации и времени съемки легко сложить маршрут твоих перемещений за последние пять лет.

detect.location

Существуют и более известные, но при этом не менее неприятные вещи.

Например, многие счетчики посещаемости вроде «Яндекс.Метрики» позволяют владельцам сайта, помимо прочего, записывать сессию пользователя — то есть писать каждое движение мыши и нажатие на кнопку. С одной стороны, ничего нелегального тут нет, с другой — стоит посмотреть такую запись своими глазами, и понимаешь, что тут что-то не так и такого механизма существовать не должно. И это не считая того, что через него в определенных случаях могут утечь пароли или платежные данные.

И таких примеров масса — если ты интересуешься темой и читаешь «Отдел К» дольше пары месяцев, то сам без труда припомнишь что-нибудь в этом духе.

Но гораздо сложнее понять, что происходит с собранными данными дальше. А ведь жизнь их насыщенна и интересна.

Торговцы привычками.

Многие собираемые данные на первый взгляд кажутся безобидными и зачастую обезличены, но связать их с человеком не так сложно, как представляется, а безобидность зависит от обстоятельств. Как думаешь, насколько безопасно делиться с кем-то ну, например, данными шагомера? По ним, в частности, легко понять, во сколько тебя нет дома и по каким дням ты возвращаешься поздно.

Однако грабители пока что до столь высоких технологий не дошли, а вот рекламщиков любая информация о твоих привычках может заинтересовать. Как часто ты куда-то ходишь? По будням или по выходным? Утром или после обеда? В какие заведения? И так далее и тому подобное.

Только в США, по подсчетам журнала Newsweek, существует несколько тысяч фирм, которые занимаются сбором, переработкой и продажей баз данных (гиганты индустрии — Acxiom и Experian оперируют миллиардными оборотами). Их основной продукт — это разного рода рейтинги, которые владельцы бизнесов могут купить и в готовом виде использовать при принятии решений.

В желающих продать данные тоже нет недостатка.

Любой бизнесмен, узнавший, что можно сделать немного денег из ничего, как минимум заинтересуется. И не думай, что главное зло здесь — бездушные корпорации.

Стартапы в этом плане чуть ли не хуже: сегодня в них работают прекрасные честные люди, а завтра может остаться только пара циничных менеджеров, пускающих с молотка последнее имущество.

Автор Newsweek отмечает важный момент: данные, собираемые брокерами, часто содержат ошибки и рейтинг может выйти неверным. Так что если кому-то вдруг откажут в кредите или не захотят принимать на работу, то, возможно, ему стоит винить не себя, а безумную систему слежки, стихийно возникшую за последние пятнадцать лет.

Твой теневой профиль.

В большинстве стран центр общественной жизни в онлайне — это Facebook, поэтому и разговоры о приватности в Сети часто крутятся вокруг него.

На первый взгляд может показаться, что Facebook неплохо заботится о сохранности личных данных и предоставляет массу настроек приватности. Поэтому технически подкованные люди часто списывают со счетов страхи и жалобы менее образованных в этом плане товарищей. Если кто-то случайно поделился с миром тем, чем делиться не хотел, значит, виноват сам — надо было вовремя головой думать.

В реальности Facebook и правда заботится о сохранности личных данных, но это скорее утверждение вроде известного в СССР афоризма «Нам нужен мир, и по возможности весь».

Как и многие социальные сети и мессенджеры, Facebook пытается захватить и сохранить столько личных данных, сколько получится.

было замечено и за «Телеграмом». Вот такой парадокс: мессенджер, который, с одной стороны, предоставляет удобные средства шифрования, с другой — не забывает сам захватить все, до чего дотянется.

Еще веселее то, что у «Фейсбука» уже так много данных, что, даже если отдельный человек никогда не имел аккаунта, его профиль все равно можно составить из информации, которую непрерывно оставляют другие люди. А «можно» в таких случаях значит, что так оно наверняка и происходит. Если алгоритмы соцсети увидят информационную дыру в форме человека, то они будут иметь ее в виду и дополнять новыми деталями.

Сотрудники Facebook страшно не любят словосочетание «теневой профиль». Конечно, приятно думать, что они просто собирают данные, которые помогут людям найти старых друзей, возобновить утерянные деловые контакты и все в таком духе.

Чуть менее приятно — помнить о том, что все это делается ради того, чтобы более эффективно продавать рекламу. А уж постоянно воображать случаи шантажа, мести или мошенничества и вовсе не хочется.

Нам при этом совершенно не важно, чего хотят Цукерберг и его сотрудники. Да, скорее всего, он жалеет, что на заре своей карьеры назвал первых пользователей Facebook обидными словами dumb fucks за то, что те оставляли на его сайте личные данные. Но изменились ли с тех пор его взгляды на жизнь? И более важный вопрос — не становятся ли его слова все более правдивыми?

Не очень отдаленное будущее.

Еще десять-пятнадцать лет назад все, о чем мы тут говорили, либо не существовало, либо не волновало большинство людей. Сейчас реакция публики потихоньку меняется, но, скорее всего, недостаточно быстро, и следующие десять-пятнадцать лет в плане приватности обещают стать крайне неприятными (или неприватными?).

Если сейчас следить проще всего в интернете, то с миниатюризацией и удешевлением электроники те же проблемы постепенно доберутся и до окружающего нас мира. Собственно, они уже потихоньку добираются, но это только начало.

Недавно все охали и ахали от фотографии сглючившего рекламного стенда в пиццерии, который детектил лица.

Волноваться надо было, когда эту штуку возили по выставкам. В статье «How low (power) can you go?» писатель Чарли Стросс отталкивается от закона Куми (вариации закона Мура, которая говорит, что энергоэффективность компьютеров удваивается каждые 18 месяцев) и рассчитывает минимально потребляемую мощность компьютеров 2032 года.

По грубым прикидкам Стросса выходит, что аналог нынешних маломощных мобильных систем на чипе с набором сенсоров через пятнадцать лет сможет питаться от солнечной батареи со стороной два-три миллиметра либо от энергии радиосигнала. И это без учета того, что могут появиться более эффективные батареи или другие способы доставки энергии.

Стросс рассуждает дальше: «Будем считать, что наш гипотетический компьютер с низким энергопотреблением при массовом производстве будет стоить 10 центов за штуку. Тогда покрыть Лондон процессорами по одному на квадратный метр к 2040 году будет стоить 150 миллионов евро, или 20 евро на человека». Столько же власти Лондона за 2007 год потратили на отдирание жвачки от дорог, так что вряд ли такой проект окажется городу не по карману.

Michigan Micro Mote — прототип крошечного компьютера с солнечной батареей. И это технологии 2015 года, а не 2034-го.

Дальше Стросс обсуждает выгоды, которые может дать компьютеризация городских поверхностей, — от суперточных прогнозов погоды до предотвращения эпидемий. Но в рамках этой статьи нас, конечно, интересует другое: тот уровень тотального наблюдения, который может дать эта почти что «умная пыль» из научной фантастики.

«Носить худи уже не поможет», — с сарказмом отмечает Стросс.

И действительно: даже если у вездесущих сенсоров не будет камер, они все равно смогут считывать каждую метку RFID или идентифицировать мобильные устройства с модулями связи. Да и собственно, почему не будет камер? Крошечные объективы, которые можно производить сразу вместе с матрицей, уже сейчас создаются в лабораторных условиях.

Память толпы.

То, к чему может потенциально привести распыление компьютеров ровным слоем по окружающей местности, Стросс называет словами panopticon singularity — по аналогии с технологической сингулярностью, которая подразумевает бесконтрольное распространение технологий.

Это иная техногенная страшилка, которая означает повсеместное наблюдение и, как следствие, несвободу.

Можно вообразить, до каких крайностей дойдет, если технологии массовой слежки попадут в руки диктаторскому режиму или религиозным фундаменталистам. Однако даже если представлять, что такую систему будет контролировать обычное, не особенно коррумпированное и не слишком зацикленное на традиционных ценностях правительство, все равно как-то не по себе.

Другой потенциальный источник повсеместной слежки — это сами люди. Вот краткая история этой технологии:

Поводы нацепить на голову камеру могут быть разные — например, стримить в Periscope или Twitch, пользоваться приложениями с дополненной реальностью или просто записывать все происходящее, чтобы иметь цифровую копию, к которой можно в любой момент обратиться за воспоминанием.

Старший исследователь Microsoft Research Гордон Белл в своей последней книге Your Life Uploaded Белл рассуждает о разных аспектах жизни общества, где все имеют документальные свидетельства всего произошедшего. Белл считает, что это хорошо: не будет преступлений, не будет невинно наказанных, а люди смогут пользоваться сверхнадежной памятью машин.

А как же приватность? Можно ли в мире будущего сделать что-то втайне от других?

Белл считает, что система должна быть построена таким образом, чтобы в любой момент можно было исключить себя из общественной памяти.

Нажимаешь волшебную кнопочку, и право смотреть запись с тобой останется, к примеру, только у полиции. Удобно, правда?

Вот тут-то и понимаешь по-настоящему, где заканчивается та дорога, на которую встал Facebook со своими теневыми профилями. Если все будет как сейчас и люди продолжат радостно загружать свои данные, то волшебная кнопка выпадения из общей памяти просто ни на что не повлияет. Ну исключил ты себя, а интеллектуальный алгоритм тут же связал все обратно из косвенных признаков.

Что делать?

…чтобы не наступило мрачное будущее, от которого вздрогнул бы даже Джордж Оруэлл?

Все мы думаем, что, наверное, кто-то там как-то, возможно, об этом позаботится. Активисты должны сказать «нет», правительства должны ввести законы, исполнительная власть — проследить, ну и так далее. Увы, истории известна масса случаев, когда эта схема неслабо сбоила.

Правительственные инициативы действительно есть — смотри, например, европейский GDPR — общий регламент по защите данных.

Это постановление регулирует сбор и хранение личной информации, и с ним Facebook уже не отделается щадящим (с учетом гигантских оборотов) штрафом в 122 миллиона евро. Отваливать придется уже 4% от выручки, то есть как минимум миллиард.

Первый этап GDPR стартует 25 мая 2018 года. Тогда-то мы и узнаем, какие у него побочные эффекты, какие обходные маневры последуют и удастся ли в реальности чего-то добиться от транснациональных корпораций. В России уже имеется не самый успешный опыт с законом «О персональных данных». Характерно, что его скромные успехи мало кого печалят («пусть лучше следят Цукерберг и Пейдж с Брином, чем товарищ полковник»).

Да и в целом есть серьезные подозрения, что правительства хотят не столько пресечь слежку, сколько приложиться к ней, а в идеале — вернуть себе монополию.

Так что гораздо лучше было бы, начни корпорации сами себя одергивать и регулировать. Увы, как мы видим на примере «Фейсбука», некоторые из них работают в ровно противоположном направлении.

Можем ли мы сделать что-то сами, кроме как судорожно пытаться скрыться, зашифровать, обфусцировать и поотключать все на свете? Я предлагаю начать с главного — стараться никогда не махать рукой и не говорить: «Ай, все равно все следят!» Не все равно, не все и не с одинаковыми последствиями. Это важно.

Источник @dapartamentK

Тот самый паноптикон.

Начнем мы не с современности, а с восемнадцатого века, из которого к нам пришло слово «паноптикон». Изначально его придумал изобретатель довольно странной вещи — тюрьмы, в которой надзиратель мог постоянно видеть каждого заключенного, а заключенные не могли бы видеть ни друг друга, ни надзирателя. Звучит как какой-то мысленный эксперимент или философская концепция, правда? Отчасти так и есть, но автор этого понятия британец Джереми Бентам был настроен предельно решительно в своем стремлении построить паноптикон в реальности.

Бентамовские чертежи паноптикона

Бентам был буквально одержим своей идеей и долго упрашивал британское и другие правительства дать ему денег на строительство тюрьмы нового типа. Он считал, что непрерывное и незаметное наблюдение положительно скажется на исправлении заключенных. К тому же такие тюрьмы было бы намного дешевле содержать. Под конец он уже и сам был готов стать главным надзирателем, но денег на строительство собрать так и не удалось.

Вдохновленная паноптиконом тюрьма на Кубе. Заброшена с 1967 года

С тех пор в разных странах было построено несколько тюрем и других заведений, вдохновленных чертежами Бентама. Но нас в этой истории, конечно, интересует другое.

Паноптикон почти сразу стал синонимом для общества тотальной слежки и контроля. Которое, кажется, строится прямо у нас на глазах.

33 бита энтропии.

Исследователь Арвинд Нараянан предложил полезный метод, который помогает измерить степень анонимности. Он назвал его «33 бита энтропии» — именно столько информации нужно знать о человеке, чтобы выделить его уникальным образом среди всего населения Земли.

Если взять за каждый бит какой-то двоичный признак, то 33 бита как раз дадут нам уникальное совпадение среди 6,6 миллиарда.

Однако следует помнить о том, что признаки обычно не двоичны и иногда достаточно всего нескольких параметров.

Возьмем для примера базу данных, где хранится почтовый индекс, пол, возраст и модель машины. Почтовый индекс ограничивает выборку в среднем до 20 тысяч человек — и это цифра для очень плотно населенного города: в Москве на одно почтовое отделение приходится 10 тысяч человек, а в среднем по России — 3,5 тысячи.

Пол ограничит выборку вдвое. Возраст — уже до нескольких сотен, если не десятков. А модель машины — всего до пары человек, а зачастую и до одного. Более редкая машина или мелкий населенный пункт могут сделать половину параметров ненужными.

Скрипты, куки и веселые трюки.

Вместо почтового индекса и модели машины можно использовать версию браузера, операционную систему, разрешение экрана и прочие параметры, которые мы оставляем каждому посещенному сайту, а рекламные сети усердно все это собирают и с легкостью отслеживают путь, привычки и предпочтения отдельных пользователей.

Вот занятный пример из мира мобильных приложений.

Каждая программа для iOS, которая получает доступ к фотографиям (например, чтобы наложить на них красивый эффект), имеет возможность за секунды просканировать всю базу и засосать метаданные. Если фотографий много, то из данных о геолокации и времени съемки легко сложить маршрут твоих перемещений за последние пять лет.

detect.location

Существуют и более известные, но при этом не менее неприятные вещи.

Например, многие счетчики посещаемости вроде «Яндекс.Метрики» позволяют владельцам сайта, помимо прочего, записывать сессию пользователя — то есть писать каждое движение мыши и нажатие на кнопку. С одной стороны, ничего нелегального тут нет, с другой — стоит посмотреть такую запись своими глазами, и понимаешь, что тут что-то не так и такого механизма существовать не должно. И это не считая того, что через него в определенных случаях могут утечь пароли или платежные данные.

И таких примеров масса — если ты интересуешься темой и читаешь «Отдел К» дольше пары месяцев, то сам без труда припомнишь что-нибудь в этом духе.

Но гораздо сложнее понять, что происходит с собранными данными дальше. А ведь жизнь их насыщенна и интересна.

Торговцы привычками.

Многие собираемые данные на первый взгляд кажутся безобидными и зачастую обезличены, но связать их с человеком не так сложно, как представляется, а безобидность зависит от обстоятельств. Как думаешь, насколько безопасно делиться с кем-то ну, например, данными шагомера? По ним, в частности, легко понять, во сколько тебя нет дома и по каким дням ты возвращаешься поздно.

Однако грабители пока что до столь высоких технологий не дошли, а вот рекламщиков любая информация о твоих привычках может заинтересовать. Как часто ты куда-то ходишь? По будням или по выходным? Утром или после обеда? В какие заведения? И так далее и тому подобное.

Только в США, по подсчетам журнала Newsweek, существует несколько тысяч фирм, которые занимаются сбором, переработкой и продажей баз данных (гиганты индустрии — Acxiom и Experian оперируют миллиардными оборотами). Их основной продукт — это разного рода рейтинги, которые владельцы бизнесов могут купить и в готовом виде использовать при принятии решений.

В желающих продать данные тоже нет недостатка.

Любой бизнесмен, узнавший, что можно сделать немного денег из ничего, как минимум заинтересуется. И не думай, что главное зло здесь — бездушные корпорации.

Стартапы в этом плане чуть ли не хуже: сегодня в них работают прекрасные честные люди, а завтра может остаться только пара циничных менеджеров, пускающих с молотка последнее имущество.

Автор Newsweek отмечает важный момент: данные, собираемые брокерами, часто содержат ошибки и рейтинг может выйти неверным. Так что если кому-то вдруг откажут в кредите или не захотят принимать на работу, то, возможно, ему стоит винить не себя, а безумную систему слежки, стихийно возникшую за последние пятнадцать лет.

Твой теневой профиль.

В большинстве стран центр общественной жизни в онлайне — это Facebook, поэтому и разговоры о приватности в Сети часто крутятся вокруг него.

На первый взгляд может показаться, что Facebook неплохо заботится о сохранности личных данных и предоставляет массу настроек приватности. Поэтому технически подкованные люди часто списывают со счетов страхи и жалобы менее образованных в этом плане товарищей. Если кто-то случайно поделился с миром тем, чем делиться не хотел, значит, виноват сам — надо было вовремя головой думать.

В реальности Facebook и правда заботится о сохранности личных данных, но это скорее утверждение вроде известного в СССР афоризма «Нам нужен мир, и по возможности весь».

Как и многие социальные сети и мессенджеры, Facebook пытается захватить и сохранить столько личных данных, сколько получится.

было замечено и за «Телеграмом». Вот такой парадокс: мессенджер, который, с одной стороны, предоставляет удобные средства шифрования, с другой — не забывает сам захватить все, до чего дотянется.

Еще веселее то, что у «Фейсбука» уже так много данных, что, даже если отдельный человек никогда не имел аккаунта, его профиль все равно можно составить из информации, которую непрерывно оставляют другие люди. А «можно» в таких случаях значит, что так оно наверняка и происходит. Если алгоритмы соцсети увидят информационную дыру в форме человека, то они будут иметь ее в виду и дополнять новыми деталями.

Сотрудники Facebook страшно не любят словосочетание «теневой профиль». Конечно, приятно думать, что они просто собирают данные, которые помогут людям найти старых друзей, возобновить утерянные деловые контакты и все в таком духе.

Чуть менее приятно — помнить о том, что все это делается ради того, чтобы более эффективно продавать рекламу. А уж постоянно воображать случаи шантажа, мести или мошенничества и вовсе не хочется.

Нам при этом совершенно не важно, чего хотят Цукерберг и его сотрудники. Да, скорее всего, он жалеет, что на заре своей карьеры назвал первых пользователей Facebook обидными словами dumb fucks за то, что те оставляли на его сайте личные данные. Но изменились ли с тех пор его взгляды на жизнь? И более важный вопрос — не становятся ли его слова все более правдивыми?

Не очень отдаленное будущее.

Еще десять-пятнадцать лет назад все, о чем мы тут говорили, либо не существовало, либо не волновало большинство людей. Сейчас реакция публики потихоньку меняется, но, скорее всего, недостаточно быстро, и следующие десять-пятнадцать лет в плане приватности обещают стать крайне неприятными (или неприватными?).

Если сейчас следить проще всего в интернете, то с миниатюризацией и удешевлением электроники те же проблемы постепенно доберутся и до окружающего нас мира. Собственно, они уже потихоньку добираются, но это только начало.

Недавно все охали и ахали от фотографии сглючившего рекламного стенда в пиццерии, который детектил лица.

Волноваться надо было, когда эту штуку возили по выставкам. В статье «How low (power) can you go?» писатель Чарли Стросс отталкивается от закона Куми (вариации закона Мура, которая говорит, что энергоэффективность компьютеров удваивается каждые 18 месяцев) и рассчитывает минимально потребляемую мощность компьютеров 2032 года.

По грубым прикидкам Стросса выходит, что аналог нынешних маломощных мобильных систем на чипе с набором сенсоров через пятнадцать лет сможет питаться от солнечной батареи со стороной два-три миллиметра либо от энергии радиосигнала. И это без учета того, что могут появиться более эффективные батареи или другие способы доставки энергии.

Стросс рассуждает дальше: «Будем считать, что наш гипотетический компьютер с низким энергопотреблением при массовом производстве будет стоить 10 центов за штуку. Тогда покрыть Лондон процессорами по одному на квадратный метр к 2040 году будет стоить 150 миллионов евро, или 20 евро на человека». Столько же власти Лондона за 2007 год потратили на отдирание жвачки от дорог, так что вряд ли такой проект окажется городу не по карману.

Michigan Micro Mote — прототип крошечного компьютера с солнечной батареей. И это технологии 2015 года, а не 2034-го.

Дальше Стросс обсуждает выгоды, которые может дать компьютеризация городских поверхностей, — от суперточных прогнозов погоды до предотвращения эпидемий. Но в рамках этой статьи нас, конечно, интересует другое: тот уровень тотального наблюдения, который может дать эта почти что «умная пыль» из научной фантастики.

«Носить худи уже не поможет», — с сарказмом отмечает Стросс.

И действительно: даже если у вездесущих сенсоров не будет камер, они все равно смогут считывать каждую метку RFID или идентифицировать мобильные устройства с модулями связи. Да и собственно, почему не будет камер? Крошечные объективы, которые можно производить сразу вместе с матрицей, уже сейчас создаются в лабораторных условиях.

Память толпы.

То, к чему может потенциально привести распыление компьютеров ровным слоем по окружающей местности, Стросс называет словами panopticon singularity — по аналогии с технологической сингулярностью, которая подразумевает бесконтрольное распространение технологий.

Это иная техногенная страшилка, которая означает повсеместное наблюдение и, как следствие, несвободу.

Можно вообразить, до каких крайностей дойдет, если технологии массовой слежки попадут в руки диктаторскому режиму или религиозным фундаменталистам. Однако даже если представлять, что такую систему будет контролировать обычное, не особенно коррумпированное и не слишком зацикленное на традиционных ценностях правительство, все равно как-то не по себе.

Другой потенциальный источник повсеместной слежки — это сами люди. Вот краткая история этой технологии:

- версия 1.0 — старушки у подъезда, которые всё про всех знают;

- версия 2.0 — прохожие, которые чуть что выхватывают из карманов телефоны, фотографируют и постят в соцсети;

- версия 3.0 — постоянно включенные камеры на голове у каждого.

Поводы нацепить на голову камеру могут быть разные — например, стримить в Periscope или Twitch, пользоваться приложениями с дополненной реальностью или просто записывать все происходящее, чтобы иметь цифровую копию, к которой можно в любой момент обратиться за воспоминанием.

Старший исследователь Microsoft Research Гордон Белл в своей последней книге Your Life Uploaded Белл рассуждает о разных аспектах жизни общества, где все имеют документальные свидетельства всего произошедшего. Белл считает, что это хорошо: не будет преступлений, не будет невинно наказанных, а люди смогут пользоваться сверхнадежной памятью машин.

А как же приватность? Можно ли в мире будущего сделать что-то втайне от других?

Белл считает, что система должна быть построена таким образом, чтобы в любой момент можно было исключить себя из общественной памяти.

Нажимаешь волшебную кнопочку, и право смотреть запись с тобой останется, к примеру, только у полиции. Удобно, правда?

Вот тут-то и понимаешь по-настоящему, где заканчивается та дорога, на которую встал Facebook со своими теневыми профилями. Если все будет как сейчас и люди продолжат радостно загружать свои данные, то волшебная кнопка выпадения из общей памяти просто ни на что не повлияет. Ну исключил ты себя, а интеллектуальный алгоритм тут же связал все обратно из косвенных признаков.

Что делать?

…чтобы не наступило мрачное будущее, от которого вздрогнул бы даже Джордж Оруэлл?

Все мы думаем, что, наверное, кто-то там как-то, возможно, об этом позаботится. Активисты должны сказать «нет», правительства должны ввести законы, исполнительная власть — проследить, ну и так далее. Увы, истории известна масса случаев, когда эта схема неслабо сбоила.

Правительственные инициативы действительно есть — смотри, например, европейский GDPR — общий регламент по защите данных.

Это постановление регулирует сбор и хранение личной информации, и с ним Facebook уже не отделается щадящим (с учетом гигантских оборотов) штрафом в 122 миллиона евро. Отваливать придется уже 4% от выручки, то есть как минимум миллиард.

Первый этап GDPR стартует 25 мая 2018 года. Тогда-то мы и узнаем, какие у него побочные эффекты, какие обходные маневры последуют и удастся ли в реальности чего-то добиться от транснациональных корпораций. В России уже имеется не самый успешный опыт с законом «О персональных данных». Характерно, что его скромные успехи мало кого печалят («пусть лучше следят Цукерберг и Пейдж с Брином, чем товарищ полковник»).

Да и в целом есть серьезные подозрения, что правительства хотят не столько пресечь слежку, сколько приложиться к ней, а в идеале — вернуть себе монополию.

Так что гораздо лучше было бы, начни корпорации сами себя одергивать и регулировать. Увы, как мы видим на примере «Фейсбука», некоторые из них работают в ровно противоположном направлении.

Можем ли мы сделать что-то сами, кроме как судорожно пытаться скрыться, зашифровать, обфусцировать и поотключать все на свете? Я предлагаю начать с главного — стараться никогда не махать рукой и не говорить: «Ай, все равно все следят!» Не все равно, не все и не с одинаковыми последствиями. Это важно.

Источник @dapartamentK